With other things to occupy their minds, both Pepsi and Coke have hung up their sparring gloves - for now. What led to this cessation in hostilities?

It wasn't long ago, when the advertising battles between the two cola majors - Pepsi and Coca Cola (Coke) - was a topic of heated discussion from drawing rooms to college canteens to local trains. While it lasted, it was fascinating. People followed the moves each brand made, every closely. They also took great interest in finding out the next move of their favourite brand. How and when would it attack or counter-attack its competitor?

During the last few years, however, both brands seem to have sobered up. The two cola brands have stopped taking pots shots at each other. There is peace and harmony in the category as if the two brands have decided to settle down in happy coexistence. What led to this ceasefire?

How it all started

Before moving ahead to explore the reasons behind this calm state of affairs, it's important to go back a few years to find out how the cola war began in this country.

It all started in 1993, when Coca Cola decided to re-enter the market for the second time (the brand had exited India in 1977, when the government wanted Coca Cola India to hand over the control to its Indian subsidiary, which implied that the company would have to reveal its secret recipe - or do away with it altogether).

Coca Cola's arch rival, Pepsi, was already present in the market for six years then. Pepsi had entered India through a joint venture (JV) with two players - Punjab Agro Industrial Corporation and Voltas India. By the time Coca Cola made its second entry, Pepsi had established itself as a brand. This was unlike other markets where Pepsi was the challenger brand and Coca Cola the leader. In India the two had swapped their positions. In this market, Pepsi was the leader and Coke the challenger.

The attributes of a challenger brand was in Pepsi's DNA and worldwide, this is what the brand was known for. In India, Pepsi could not deviate from its original approach even though it was a leader brand in this market. It kept on instigating Coke even in India as it had done in other markets. When Coke entered India, Pepsi ran a print campaign across national dailies which said "We invite you to taste Coke'. This was followed by another campaign - Coke is the registered trade mark of Coca-Cola and Pepsi is the choice of next generation. Pepsi also took a dig at Coke with 'Nothing official about it' campaign when Coke became the official partner of the 1996 Cricket World Cup.

That set the tone for more pitched battles. Pepsi, in spite of being the leader, connected well with the consumers with its challenging communication. In a way, Pepsi acknowledged the fact that though it had the bigger share, in terms of image Coke was the benchmark brand.

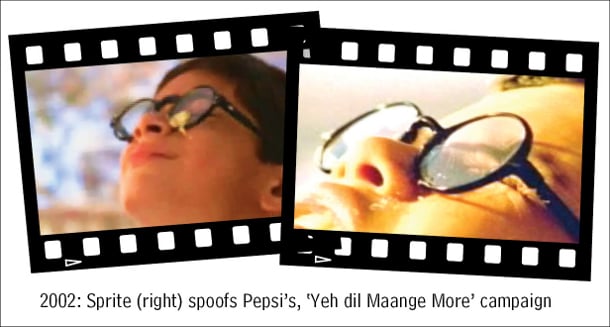

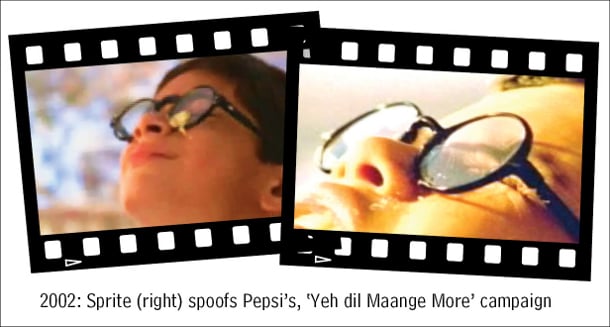

The war of advertising wasn't restricted only to colas. If Pepsi attacked Coke, the latter retaliated with a campaign for Sprite (the clear drink) against Pepsi and Mountain Dew. Pepsico, in return, would attack Thums Up with Mountain Dew and Pepsi.

The common enemy

For the first few years, the two global cola brands were busy expanding their individual reach and market until 2003 when the pesticide controversy blew up in their faces. A study released by the Centre for Science & Environment (CSE) in 2003 stated that the pesticide residue in cola drinks was higher than the permissible limit.

It was a huge blow and neither brand was prepared for this. The brands thus did not have a ready solution to fall back on but decided to experiment to circumvent the problem. Each of them started by launching local flavours. While Coca-Cola launched green apple and watermelon variants of Fanta along with masala soda drink, Rimzim and Portello, Pepsi's answer was the launch of Mirinda Brown Apple. Unfortunately, these brands sank without a trace.

Next, the two brands reduced the size of the bottle from the usual 300 ml to 200 ml and lowered the price from Rs. 10 to Rs. 5. This worked. The price reduction was followed by several campaigns. Coke tried to reassert its supremacy through 'Thanda matlab Coca-Cola', while Pepsi kept harping on its youth quotient 'Yeh dil maange more', 'Yeh pyaas hain badi' (in 2004) and 'Oye Bubbly' (in 2005).

As luck would have it, in 2006, the pesticide controversy reared its ugly head yet again. The CSE reviewed its study and came up with the same conclusions. According to an industry observer, "Both Pepsi and Coca-Cola had just risen from the old controversy and the fresh controversy kind of broke the backbone of the cola category."

Both Pepsi and Coke then decided it was time to do something. And the best way they knew to counter the bad publicity was by using advertising. Both rolled out campaigns that had people of eminence endorsing the safety factor. Pepsi launched 'Aapki Pepsi safe hain', featuring Rajeev Bakshi, then chairman of PepsiCo India who talked about how the beverage is tested at various levels and consumer safety ensured at all stages of manufacturing.

Meanwhile Coca-Cola continued with the campaign, 'Thanda matlab Coca-Cola'. It launched a TVC in which Aamir Khan, playing a Bengali character, goes to a restaurant to have food. Even as his wife orders Thanda (Coke), Khan flares up and talks about how the cola is harmful. However, his wife rebukes him and then says that people should not fall prey to wrong information, when the company is ensuring safety at every level. To some extent, the damage control blitzkrieg helped rein in the bad publicity for both players.

It was also the time when the duo decided that, in order to survive, they had to fight together and not against each other. An unofficial agreement was made between two, that they would will not attack each on Indian soil. After all, they had a common enemy now.

Last stand

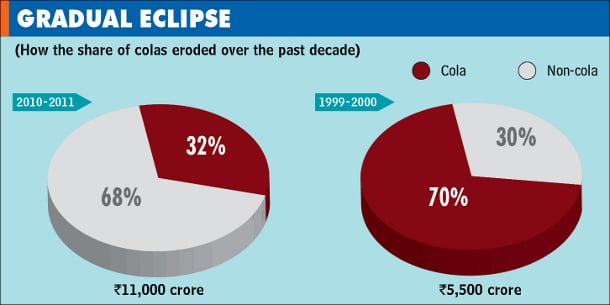

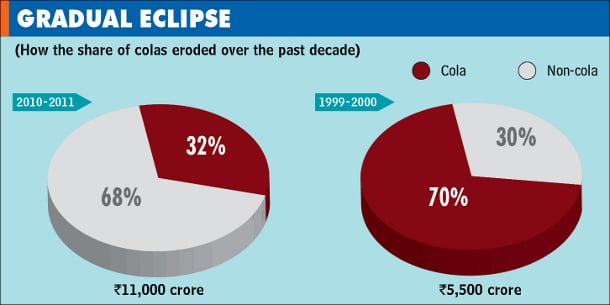

The agreement was a relationship of convenience and mutual existence. In fact, a small spark could have changed the situation and the Cola brands would have headed into their next battle.However, other things were beginning to change. Colas, which represented the youth brigade at one point of time, lost their relevance not only amongst the youth but also with the general consumers. The category which was once symbolic of a good life, could not sustain that image.

The youth brigade discovered other avenues to show off their attitudes. Technology brands took over, whether it was mobile phones, cellular services or social networking. Says Santosh Desai, CEO, Future Brands, "The cola brands weren't a defining category any longer. Today, a cola brand or a chips brand stand at the same pedestal, which the people consume when they feel like."

As the youth lost interest in the colas, the war between the brands made no sense. "The idea of spoofing a competitive brand is always to instigate the consumers to start a conversation around the brand. But if the people are not enthused about the brand or the category, it will fail to strike a conversation," says Jitender Dabas, EV-P, planning, McCann Erickson.

Close on the heels of these factors came a third obstacle. The increasing health consciousness among consumers dealt another blow. Calorie conscious consumers frowned upon the practice of popping a Pepsi or a Coke every now and then. They started favouring clear and flavoured drinks over colas. The fact that Sprite, today, holds the No.1 position in the flavoured carbonated beverages category proves this.

The growing preference of other drinks over cola was restricted not just to the consumers. Even the holding companies for the two brands changed their strategies accordingly. They realised that the growth was not in colas but other beverages and products. The companies banked on other product categories for growth.

From 2006 onwards, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola focused on developing and promoting a portfolio of products which included clear sparkling beverages such as Sprite, Limca and Mountain Dew, juices - Tropicana and Minute Maid, mango-based drinks Slice and Maaza and the orange flavoured Fanta and Mirinda. Explains a senior industry observer, "This holds true more in case of Coca Cola India than PepsiCo India. For PepsiCo, the flagship brand is still largest selling brand, but for Coca Cola India, other brands have taken the lead," he explains.

According to industry estimates, the overall size of the beverage industry is Rs. 11,000 crore, of which cola constitutes Rs. 3,500 crore and the cloudy lemon and lime drink category about Rs. 4,500 crore. The orange drink category is worth Rs. 2,500 crore, while the rest is soda.

Telecom is the new Cola

With colas losing their relevance in the everyday conversations of the youth, it was telecom that took up the slack. The level of engagement between the product and the consumer was much higher in the latter. Be it the handset brand or the cellular service provider, the involvement of a telecom brand in a consumer's life is much deeper. There is an interaction on a daily basis while colas are consumed less often.

This change in thought affected the advertising and marketing community as well. The number of celebrities endorsing cola and telecom depicts the true picture. For instance, if five years ago, colas queued up a long line of the who's who among celebrities to endorse its brand, it is the telecom players who have taken a lead on this today.

Besides, colas aren't largest spenders any more. Telecom players have taken a lead in this. Today, an agency is known for the telecom brand it handles. In the good old days, it was known for the cola brand it serviced. But many feel that the phenomenon is not directly linked with spends. For instance, insurance as a category spends heavily, but it still isn't the defining category for the community.

Moreover, the marketing and communication processes had evolved in the new era. The cola brands were at the forefront when the country was experiencing the early days of guerrilla marketing. With time, many new ways of modern marketing warfare have evolved. "Taking a public dig at each other to outshine the other isn't the 'in' thing anymore. Today's consumers are discerning enough to move beyond shouting matches and gravitate towards meaningful engagements," says Anirban Choudhury, senior vice-president, DDB Mudra.

There are some categories such as health drinks or detergents where competitive claims at a functional level crop up, at times, as marketing communication planks. But conversations in such categories are less animated than in a cola or a telecom brand. For instance, the youth would not like to comment on the Rin Vs Tide war on a social networking platform because he doesn't feel involved enough.

There is also a point of view that the cola war is not yet over. There might be a lull at the moment but the storm could start any moment. That, as they say, is another story.

Source

It wasn't long ago, when the advertising battles between the two cola majors - Pepsi and Coca Cola (Coke) - was a topic of heated discussion from drawing rooms to college canteens to local trains. While it lasted, it was fascinating. People followed the moves each brand made, every closely. They also took great interest in finding out the next move of their favourite brand. How and when would it attack or counter-attack its competitor?

During the last few years, however, both brands seem to have sobered up. The two cola brands have stopped taking pots shots at each other. There is peace and harmony in the category as if the two brands have decided to settle down in happy coexistence. What led to this ceasefire?

How it all started

Before moving ahead to explore the reasons behind this calm state of affairs, it's important to go back a few years to find out how the cola war began in this country.

It all started in 1993, when Coca Cola decided to re-enter the market for the second time (the brand had exited India in 1977, when the government wanted Coca Cola India to hand over the control to its Indian subsidiary, which implied that the company would have to reveal its secret recipe - or do away with it altogether).

Coca Cola's arch rival, Pepsi, was already present in the market for six years then. Pepsi had entered India through a joint venture (JV) with two players - Punjab Agro Industrial Corporation and Voltas India. By the time Coca Cola made its second entry, Pepsi had established itself as a brand. This was unlike other markets where Pepsi was the challenger brand and Coca Cola the leader. In India the two had swapped their positions. In this market, Pepsi was the leader and Coke the challenger.

The attributes of a challenger brand was in Pepsi's DNA and worldwide, this is what the brand was known for. In India, Pepsi could not deviate from its original approach even though it was a leader brand in this market. It kept on instigating Coke even in India as it had done in other markets. When Coke entered India, Pepsi ran a print campaign across national dailies which said "We invite you to taste Coke'. This was followed by another campaign - Coke is the registered trade mark of Coca-Cola and Pepsi is the choice of next generation. Pepsi also took a dig at Coke with 'Nothing official about it' campaign when Coke became the official partner of the 1996 Cricket World Cup.

That set the tone for more pitched battles. Pepsi, in spite of being the leader, connected well with the consumers with its challenging communication. In a way, Pepsi acknowledged the fact that though it had the bigger share, in terms of image Coke was the benchmark brand.

The war of advertising wasn't restricted only to colas. If Pepsi attacked Coke, the latter retaliated with a campaign for Sprite (the clear drink) against Pepsi and Mountain Dew. Pepsico, in return, would attack Thums Up with Mountain Dew and Pepsi.

The common enemy

For the first few years, the two global cola brands were busy expanding their individual reach and market until 2003 when the pesticide controversy blew up in their faces. A study released by the Centre for Science & Environment (CSE) in 2003 stated that the pesticide residue in cola drinks was higher than the permissible limit.

It was a huge blow and neither brand was prepared for this. The brands thus did not have a ready solution to fall back on but decided to experiment to circumvent the problem. Each of them started by launching local flavours. While Coca-Cola launched green apple and watermelon variants of Fanta along with masala soda drink, Rimzim and Portello, Pepsi's answer was the launch of Mirinda Brown Apple. Unfortunately, these brands sank without a trace.

Next, the two brands reduced the size of the bottle from the usual 300 ml to 200 ml and lowered the price from Rs. 10 to Rs. 5. This worked. The price reduction was followed by several campaigns. Coke tried to reassert its supremacy through 'Thanda matlab Coca-Cola', while Pepsi kept harping on its youth quotient 'Yeh dil maange more', 'Yeh pyaas hain badi' (in 2004) and 'Oye Bubbly' (in 2005).

As luck would have it, in 2006, the pesticide controversy reared its ugly head yet again. The CSE reviewed its study and came up with the same conclusions. According to an industry observer, "Both Pepsi and Coca-Cola had just risen from the old controversy and the fresh controversy kind of broke the backbone of the cola category."

Both Pepsi and Coke then decided it was time to do something. And the best way they knew to counter the bad publicity was by using advertising. Both rolled out campaigns that had people of eminence endorsing the safety factor. Pepsi launched 'Aapki Pepsi safe hain', featuring Rajeev Bakshi, then chairman of PepsiCo India who talked about how the beverage is tested at various levels and consumer safety ensured at all stages of manufacturing.

Meanwhile Coca-Cola continued with the campaign, 'Thanda matlab Coca-Cola'. It launched a TVC in which Aamir Khan, playing a Bengali character, goes to a restaurant to have food. Even as his wife orders Thanda (Coke), Khan flares up and talks about how the cola is harmful. However, his wife rebukes him and then says that people should not fall prey to wrong information, when the company is ensuring safety at every level. To some extent, the damage control blitzkrieg helped rein in the bad publicity for both players.

It was also the time when the duo decided that, in order to survive, they had to fight together and not against each other. An unofficial agreement was made between two, that they would will not attack each on Indian soil. After all, they had a common enemy now.

Last stand

The agreement was a relationship of convenience and mutual existence. In fact, a small spark could have changed the situation and the Cola brands would have headed into their next battle.However, other things were beginning to change. Colas, which represented the youth brigade at one point of time, lost their relevance not only amongst the youth but also with the general consumers. The category which was once symbolic of a good life, could not sustain that image.

The youth brigade discovered other avenues to show off their attitudes. Technology brands took over, whether it was mobile phones, cellular services or social networking. Says Santosh Desai, CEO, Future Brands, "The cola brands weren't a defining category any longer. Today, a cola brand or a chips brand stand at the same pedestal, which the people consume when they feel like."

As the youth lost interest in the colas, the war between the brands made no sense. "The idea of spoofing a competitive brand is always to instigate the consumers to start a conversation around the brand. But if the people are not enthused about the brand or the category, it will fail to strike a conversation," says Jitender Dabas, EV-P, planning, McCann Erickson.

Close on the heels of these factors came a third obstacle. The increasing health consciousness among consumers dealt another blow. Calorie conscious consumers frowned upon the practice of popping a Pepsi or a Coke every now and then. They started favouring clear and flavoured drinks over colas. The fact that Sprite, today, holds the No.1 position in the flavoured carbonated beverages category proves this.

The growing preference of other drinks over cola was restricted not just to the consumers. Even the holding companies for the two brands changed their strategies accordingly. They realised that the growth was not in colas but other beverages and products. The companies banked on other product categories for growth.

From 2006 onwards, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola focused on developing and promoting a portfolio of products which included clear sparkling beverages such as Sprite, Limca and Mountain Dew, juices - Tropicana and Minute Maid, mango-based drinks Slice and Maaza and the orange flavoured Fanta and Mirinda. Explains a senior industry observer, "This holds true more in case of Coca Cola India than PepsiCo India. For PepsiCo, the flagship brand is still largest selling brand, but for Coca Cola India, other brands have taken the lead," he explains.

According to industry estimates, the overall size of the beverage industry is Rs. 11,000 crore, of which cola constitutes Rs. 3,500 crore and the cloudy lemon and lime drink category about Rs. 4,500 crore. The orange drink category is worth Rs. 2,500 crore, while the rest is soda.

Telecom is the new Cola

With colas losing their relevance in the everyday conversations of the youth, it was telecom that took up the slack. The level of engagement between the product and the consumer was much higher in the latter. Be it the handset brand or the cellular service provider, the involvement of a telecom brand in a consumer's life is much deeper. There is an interaction on a daily basis while colas are consumed less often.

This change in thought affected the advertising and marketing community as well. The number of celebrities endorsing cola and telecom depicts the true picture. For instance, if five years ago, colas queued up a long line of the who's who among celebrities to endorse its brand, it is the telecom players who have taken a lead on this today.

Besides, colas aren't largest spenders any more. Telecom players have taken a lead in this. Today, an agency is known for the telecom brand it handles. In the good old days, it was known for the cola brand it serviced. But many feel that the phenomenon is not directly linked with spends. For instance, insurance as a category spends heavily, but it still isn't the defining category for the community.

Moreover, the marketing and communication processes had evolved in the new era. The cola brands were at the forefront when the country was experiencing the early days of guerrilla marketing. With time, many new ways of modern marketing warfare have evolved. "Taking a public dig at each other to outshine the other isn't the 'in' thing anymore. Today's consumers are discerning enough to move beyond shouting matches and gravitate towards meaningful engagements," says Anirban Choudhury, senior vice-president, DDB Mudra.

There are some categories such as health drinks or detergents where competitive claims at a functional level crop up, at times, as marketing communication planks. But conversations in such categories are less animated than in a cola or a telecom brand. For instance, the youth would not like to comment on the Rin Vs Tide war on a social networking platform because he doesn't feel involved enough.

There is also a point of view that the cola war is not yet over. There might be a lull at the moment but the storm could start any moment. That, as they say, is another story.

Source